In the beginning, the story goes, there was the Dark, and then there was Fire. In Judeo-Christian myth, the first thing that God does is make light to drive out the nothingness of the darkness. Much of human achievement is based on the harnessing of fire: the ability to cook food, to stay warm, and travel to space. Something to sit around and tell stories. The language of creativity is the language of the flame; inspiration is a “spark.” It was impossible for me not to think about this kind of stuff when I was playing The Midnight Walk, a dark puzzle-horror adventure with an eerie stop-motion animation style that demands comparison to Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. But developer MoonHood Studios knows that fire doesn’t just light the way forward. It consumes, it burns, it destroys. And a lit match, beautiful as it is, can burn down the world if it’s in the wrong place at the wrong time. The Midnight Walk isn’t mechanically complex, but its story goes places. As I walked through its stunning, often emotionally devastating world, I was mostly just happy to be walking the bleak road it laid before me.

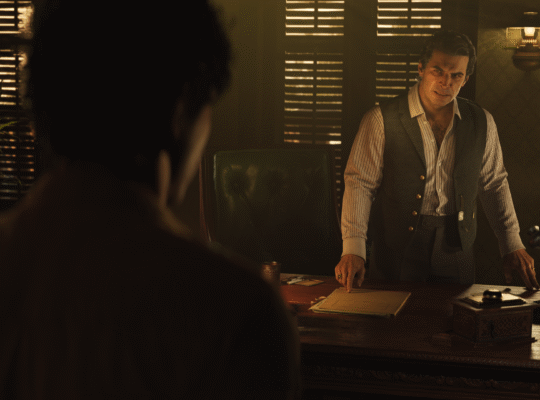

Its eight-hour journey opens with your character, the Burnt One, rising from a grave and accepting eyes and ears from another creature to be able to see and hear. At first, your mission isn’t clear; you’re just trying to survive. The world of The Midnight Walk is a place of eternal night, stalked by crawlers – creatures with too many limbs, whose movement is staggered, stuttery, and wrong. You run from them, hide from them in wardrobes, close your eyes to remove doors. Light a match, light a candle, light the way. Close your eyes and listen, and something hidden might reveal itself.

Your methods for interacting with the world are limited but consistent, and The Midnight Walk builds on them subtly, twisting them in interesting ways. A match can light a candle to solve a puzzle, but it can light your way, too. A wardrobe can hide you from the crawlers, and serve as a doorway between to other wardrobes. A gun that shoots matches can help light candles and solve puzzles from afar. Look something in the eye before closing yours, and you’ll open them to find the thing blocking your path is gone. The world tends to change when you aren’t looking, or you might have been transported. It’s simple stuff, but it’s interesting because of the ways The Midnight Walk constantly plays with the rules, modifying and adding and shaping new things atop the old, often in ways I didn’t expect (and don’t want to spoil here).

So the gameplay, simple as it is, intrigues, even if there are stumbles on this journey. Sometimes, you’re forced into awkward “sneak away from the scary Crawlers and/or Grinners” segments, which can be frustrating, but checkpoints are generous and this is little more than an annoyance at worst.

The Midnight Walk finds its soul when you meet Potboy, a small living piece of pottery capable of carrying fire – the most precious resource in a world without a sun. At first, Potboy is afraid of you, and who can blame him? The night is dark and hungry and wants to swallow him whole because the monsters like fire, too. They like the taste.

But once you get him to trust you — the way to a Potboy’s heart is through his stomach — the story really kicks in. Your job, as a Burnt One, is to escort him to Moon Mountain, where you might fix things to make a world not dominated by The Dark Itself. The story, of course, is more complicated than that. You’ll see many broken Potboys on your way, and several sarcophagi ready to resurrect you should you fall. It’s made clear that all of this has happened before, and all of it will happen again. If you’re careful and diligent you can suss out the truth of things, and whether or not all of this is worth it.

After a while, I began to worry when Potboy would run off or get ahead of me, or we were otherwise separated. He was my charge, yes, but he was also my companion, and this world was unkind. If nothing else, I wanted him to be okay. When you command him to light something or stand somewhere, it feels like he obeys because he trusts you – it’s the way he looks back, to make sure you’re still there and that everything’s okay. I wanted to be worthy of that.

One of the things I admire most about The Midnight Walk is how unwilling it is to stop and explain things to you. The characters in this world speak to you like they live here, not like they’re dispensing lore to the uninitiated, and even the narration you’ll encounter is more concerned with telling a story than making sure you know what every word means. Understanding comes from paying attention, from finding the Shellphones scattered throughout the world, and listening to the stories stored in them. They often don’t tell you who is speaking. You have to figure that out for yourself. In doing that, you begin to understand what this world is, how it came to be this way, and your place in it.

And that’s where The Midnight Walk sings for me: In its story, and in its characters. Each one of them was modeled in real-world clay and crafting materials, then scanned in and animated to resemble traditional stop motion techniques. There are the two-headed Soothsayers who worship the Fire and try to guide you along its path, dispensing their wisdom before disappearing. The enigmatic Soulfisher, said to be older than almost everything meets you by any fire on the road, to offer companionship and advice. He seems like he’s waiting for something. Housy, your walking house, who serves as a companion, a home for the things you find, and a respite from The Dark Itself. And there are more – some you’ll meet long before you understand who they are or what they’re doing, and others will become old friends or strange, threatening acquaintances.

It’s how these characters interact, and the stories that you see as you travel toward Moon Mountain, that make The Midnight Walk memorable. A village of disembodied heads, defined by their past sins, hoping to avoid retribution. A creature, the last of its kind, consumed by grief. A town destroyed by a misplaced act of revenge, hoping to put its ghosts to rest. A little girl who lit matches because they reminded her of the stars. One of the stories, The Tale of the Craftman’s Heart, didn’t quite hit me as hard as the ones that preceded or followed it, mostly because the story is told to you rather than something you experience, but even that had its moment.

Those stories, even when flawed, are what make this a game drowning in grief, loss, fear, and misunderstanding. This is a world whose boundaries are drawn by pain. You can make none of it right; the past is the past. But you can light a match and ease that pain, offer warmth and comfort to a soul in need. Potboy can help restore the fires that have gone out. Together, you can move the needle, just a little. You can bear witness. And these stories are worth hearing.

We overuse, and often overvalue, the word “cinematic” when we talk about video games, but The Midnight Walk is cinematic in a way most games aren’t and few attempt. It doesn’t do this by reveling in dialogue or smothering you in cutscenes. Instead, it sets a scene, draws the eye, fools you into turning your gaze just so and allows you to feel that all of it is organically unfolding when in fact it has been carefully crafted to seem that way. It is one of the most visually arresting games I’ve ever played, but always in service to the story, the world, the characters. The Midnight Walk supports VR (via Steam VR or PlayStation VR2), and while I didn’t get to play it that way, I imagine it’s stunning. That said, there are times that The Midnight Walk limits how you can move so that it can present an image or a scene just so, and while I can’t particularly fault what The Midnight Walk wants to show me, the loss of control and invisible barriers can feel weird.

Even its flaws, however, barely affected the way I felt when I saw both of The Midnight Walk’s endings, and the game itself. I vastly prefer one to the other, and I think anyone who sees both will know which I mean immediately. The world is more than it seems and this story is complex, and I feel only one reflects that. But the other feels so true, and my time with The Midnight Walk affected me so much that these flaws feel like roots you might trip over during a hike in the woods, or a pebble that worms its way into your shoe. Perhaps the experience is less for it, but it’s not what you’ll remember.